In 1811, Sir Walter Scott, prolific novelist, poet, and creator of the classic Scottish identity, purchased the small farm known to locals as Cartleyhole (read: muddy hole). With an imagination that made him the first English-language author to achieve international fame, Scott set about transforming what he described as a “bare haugh and bleak bank by the side of the Tweed” into a vision. His first order of business was to rename the place Abbotsford after the abbots of nearby Melrose Abbey who used to cross the River Tweed at the ford below the house. In the years to follow, Abbotsford grew into a rambling, whimsical, picturesque manse that would ultimately bankrupt the wordsmith, for such is the capriciousness of living upon the written word.

Standing just to the west of Melrose town, Abbotsford makes for an obvious and worthy visit in the heart of the central Borders. With only a few days in the region on my last pass through the Borders I had missed Abbotsford, but on this trip it stood near the top of my list. On a cloudless spring day I pulled into the gravel parking lot to visit the recently refurbished visitor center and experience Abbotsford.

Abbotsford is privately owned so you will not be able to use any National Trust for Scotland or Historic Scotland visitor passes, and while the entry fee is fairly hefty I was happy to learn that it is also well worth the cost. The brand new visitor center is a monument to the life of Sir Walter Scott, with beautiful exhibits weaving tales around various and sundry artifacts from his life. Here you’ll find rare books and letters from Scott’s library, paintings, engravings, personal possessions, manuscripts, and the egg timer he used to help him write his way out of the £126,000 debt he incurred after his publisher collapsed.

The grounds around the manor house are expertly manicured with neat paths winding around the house. The backyard is a wide, green sward that rolls downhill to the River Tweed just a couple hundred yards distant.

While Abbotsford is undoubtedly beautiful to behold from the outside, the interior of the house is something out of legend. The intricately carved wooden walls of the entrance hall are bedecked with suits of armor, swords, painted coat-of-arms, horns from a variety of animals, and all manner of paraphernalia one would expect of an antiquarian like Sir Walter Scott. A great stone fireplace stands in the center of the room that was carved by the local smiths of Darnick, and some of the oak panels on the walls are scavenged from Dunfermline Abbey and other historical sites. Scott had an eye for the theatrical and he hired a designer to give the entrance hall a weather-beaten appearance.

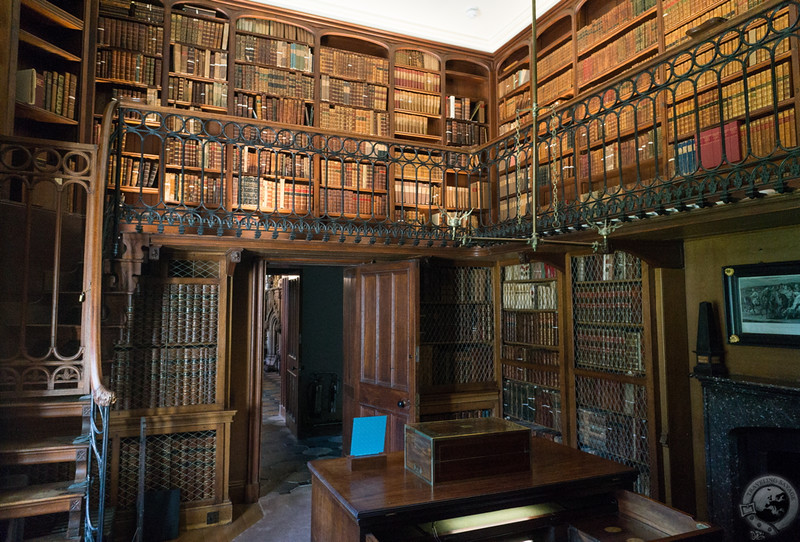

There are a limited number of rooms in Abbotsford open to the public. The first stop after passing through the entrance hall is Scott’s study, a wonderfully atmospheric room crammed with books that he used as his private sanctum. He wrote his later novels in this room, a place he could descend to through a hidden door directly from his bed chamber. The adjoining library is an immense room encompassing the length of Scott’s life and the breadth of his interests, from literary chapbooks he collected as a child to all the reference manuals he used to develop the land around Abbotsford to gifts famous authors around the world like the Brothers Grimm and Washington Irving sent him.

I spent a long time in this room, browsing the titles behind the wire screen and wondering – easily – what it must have been like to see this place as a functional space for writing and reading. I was surprised to find manuscripts on witchcraft and demonology among the shelves, and I later learned that Scott came into possession of Rosicrucian manuscripts brimming with alchemical knowledge meant for only the most clandestine types. What an interesting man!

I passed through the Chinese drawing room with its turquoise and floral wallpaper into a place that drew me like an iron filing to a magnet: The armory. Countless daggers, swords, pistols, rifles, and more arcane bladed and ballistic weapons hung upon the walls in glorious display. Among the treasures here are Rob Roy’s gun, sword, dirk, and sporran, the Marquis of Montrose’s sword, a Spanish flintlock, and the blunderbuss he used to hunt the grounds of Abbotsford. Weapon collecting, perhaps, was the financial downfall of Sir Walter Scott, but what a collection he acquired.

Passing through the bright dining room I exited onto the grounds behind Abbotsford and made my way to the banks of the Tweed. It’s not hard to imagine why Scott bought this parcel of land. It is a beautiful span along the calm Tweed, and the beautiful mansion he built on the hill opposite is a worthy counterpart.

During his life, Sir Walter Scott oversaw two phases of Abbotsford’s renovation (a third happened many years after his death). In 1824, after living in the “finished” house for only a year, a UK-wide banking crisis caused the collapse of his publisher, in which Scott had financial interest. He acquired a huge amount of debt that publicly ruined him, but rather than accept charity from his legions of supporters, he put Abbotsford and his income in a trust belonging to his creditors and vowed to write himself out of debt. It seems to me a prideful moment, for after seven years of furious writing and prolific output his health was failing. He died in 1832, at Abbotsford, still in debt.

Happily for his family, his novels continued to sell and the debt was discharged not long after his death. Happily for those of us who value culture, too, for without Sir Walter Scott Scotland would be a poorer place and our minds a shade darker.

[…] east of Abbotsford lies one of the Scottish Borders’s greatest viewpoints: Scott’s View. This was the […]