Over the last couple of weeks I’ve written about Strathearn Distillery and Wolfburn Distillery (the 600th post on Traveling Savage!), and I’m continuing distillery month with a look at another Caithness distillery: The venerable Old Pulteney Distillery in Wick. Since its founding in 1826 Old Pulteney has been one of the more difficult distilleries to visit in Scotland due to its geographical location in the far northeast hinge of the highlands. When the distillery was established everything was brought in by sea — barley, barrels, even men — and the finished whisky left by the same means. This heritage has given Old Pulteney’s whisky the moniker ‘The Maritime Malt,’ and as I would find out there’s more to this name than the history.

My visit to Old Pulteney last summer almost didn’t happen for the second time. My first attempt was stymied thanks to a road closure that prevented a visit en route to Orkney, and this time the distillery was undergoing significant refurbishment, including replacing all the washbacks, dismantling the stills, and renovating the visitors center. Thankfully the kind folks at Old Pulteney didn’t bat an eye and were happy to lead my dad and me around the place there in the heart of Wick. This situation in town is itself unique. Out of all Scotland’s distilleries, only Oban, Springbank, and Bowmore also operate within a town.

In 1826 James Henderson founded Old Pulteney Distillery at the heigh of Wick’s herring boom. There were no roads to Wick at this time so the town was frequented by shiploads of sailors surely thirsty after a hard day on the cold North Sea. The town quickly became renowned for the barrels of silver herring and gold whisky that left the port in vast numbers. Life continued normally until the 1920s when Wick became a ‘dry’ town as a result of the temperance movement. Such sadistic practice could never last — the sailors traveled to Thurso and drank up seas of whisky or went into the hills for moonshine — but it took a whopping 25 years, until 1947, before it was repealed. Prohibition and economic depression led Old Pulteney to become mothballed in 1930, and it wasn’t until 1951 that demand for whisky in Europe resulted in the reopening of Old Pulteney. The last 65 years have been a golden age.

The name Old Pulteney comes from Pulteneytown, a once-distinct town, now part of Wick, named after Sir William Pulteney, governor of the British Fisheries Society. The ownership of Old Pulteney Distillery has changed hands many times over the years, and prior to the 1990s most of the spirit was used for blends. These days 60% of the spirit they produce is reserved for single malts while the other 40% is sold off as commodity for cash flow, though I think you’ll find a healthy dose of Old Pulteney in Ballantine’s blended Scotch.

The distillery was silent during my visit, but I still had the opportunity to wander its buildings and grounds to get a sense of the place. It’s far smaller than I had imagined. When you see a bottle on your local store’s shelves half a world away you can’t help but think the distillery must be a huge place for such distribution, but just a single pair of stills produces 1.3 million liters each year at Old Pulteney. In fact, our guide, Sandy, referred to Old Pulteney as a ‘craft distillery.’

We entered the mash house to find the roof had been removed to enable the replacement of the washbacks. Old Pulteney uses two types of plain malted barley, one of which is Concerto, and no peat! Thirty tons of malted barley arrive from Inverness to enter their hoppers before mashing begins. Old Pulteney used to malt their own barley and cooper their barrels, but as with most distilleries these parts of the process have been outsourced. Five tons of the barley is milled to the industry standard 70/20/10 grist and added to the mash tun where it’s washed four times — that’s a lot — with water from Loch Hempriggs a few miles away. The third and fourth washes serve as the basis of the next mash’s first wash. The first wash is allowed to soak for a good long two hours plus, and each subsequent wash is at a higher temperature and a shorter soak. After mashing they collect 23,500 liters of sugary wort ready for fermentation.

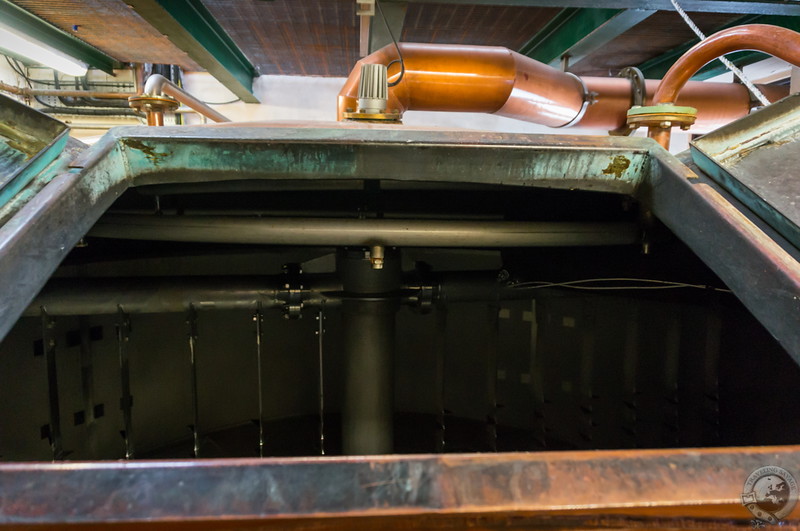

The time was right to change the washbacks. The oldest one hailed from 1920 while the newest one was more than 40 years old. All five washbacks had been removed and in went six new stainless steel washbacks with viewing hatches. The fermentation process runs about 50 hours using 20-25kg of dry distiller’s yeast, and they ferment dry so the resulting beer is quite strong.

Both of Old Pulteney’s still were dismantled for cleaning and refitting. Most of the wash still remained in place, however, and it was quite distinctive with a huge boil (reflux) ball in the neck of the still. This feature increases the copper surface area, increasing heat emission from the still and the condensation of droplets back into the pot, thereby producing a lighter spirit. The wash still was too big to be installed in the still house so they had to cut down the swan neck to make it fit. That sounds like a nightmare when you consider that every inch of copper and the angle of the swan neck have a marked influence on the character and body of the whisky. You hear these stories at distilleries all over Scotland and they become serendipitous qualities that make the spirit unique.

The low wines that come off the wash still are cooled in traditional worm tubs and register 20% ABV. These low wines are added to the spirit still with the feints from previous runnings, and after 10 minutes of foreshots the heart cut of Old Pulteney begins at 68% ABV. The heart runs for about four hours before they switch to the tails and finish off the distillation. Of the 23,500 liters of wort only 2,500 liters make the heart cut and enter barrels for aging. The rest is saved and redistilled with new batches of low wines. It’s worth noting that nothing is mechanized at Old Pulteney except parts of the mash tun’s temperature operation. The distillers here use the spirit safe to check hydrometer readings and turn the handles from heads to heart to tails while checking the boil level in each still’s window.

As we walked to the filling store and warehouses I got a look at the dismantled spirit still sitting in the yard. Loads of ex-Bourbon casks from Buffalo Trace, Jack Daniels, and Jim Beam hugged various buildings’ walls for most of Old Pulteney is aged in Bourbon casks.

All of Old Pulteney’s single malt is aged on site. The biggest warehouse is racked nine casks high and holds 10,000 casks. The other 15,000 casks are spread around the distillery’s other warehouses. It’s a delightful smell in here with the added complexity of the salty sea air. We pass through another warehouse loaded with Oloroso and Fino Sherry butts, which are primarily used for Old Pulteney’s older expressions.

We returned to attractive tasting room filled with exhibits on Old Pulteney’s history and whisky and took a seat before a trio of their standard expressions. My dad, a canny man indeed, asked if we might have a taste of their newmake, perhaps wishing to compare it to Wolfburn’s amazing unaged spirit, and we were rewarded for the inquiry. The newmake was quite fruity and soft with clear cereal notes and just a touch of punchiness on the finish. Then we moved on through the entry-level 12 Year Old, which comes in at 40% ABV having aged in 100% ex-Bourbon casks. The dram has a rich amber color with a sweet, briny nose. The taste is well-rounded and balanced between citrus, vanilla, honey, and a dry, woody note inflected with seawater. Very drinkable.

The 17 Year Old, at 46% ABV, is composed of 85% first-fill ex-Bourbon casks and 15% Sherry butts. Green apples, butterscotch, pear drops, and fudge predominate. This is a light, tasty whisky that opens up to red fruit from the Sherry with a touch of water. The 21 Year Old is something special. Also at 46% ABV, this dram comes from 35% Fino Sherry butts and 65% first-fill ex-Bourbon casks and is redolent of Christmas cake. Raisins and demerara sugar bloom on the nose ahead of spicy, woody notes. It’s mouth-watering. The palate delivers green apple, coconut, and a slight saltiness/brininess with hints of honey and vanilla. The complex palate has a long, dry finish. This whisky won best whisky in the world in 2012 from Jim Murray.

During the tasting we chatted with various Old Pulteney personnel, and each one seemed to bring out another expression, from Duncansby Head (a travel retail bottle that’s a mix of 60/40 Sherry/Bourbon), Pentland Skerries (A Sherry-only travel retail bottle), 1990 Vintage (a little smokey from aging in ex-Laphroaig casks), and their cask strength 18 Year Old Bourbon-aged whisky. Each one was delicious, complex, and unique, and I left really astounded by Old Pulteney’s quality and range — and with a bottle of the 21 Year Old in tow.

I’m sure the distillery is back together and running as usual these days, and it would be foolish to miss it on any trip including the North Coast 500 or a visit to the Orkney Islands. Old Pulteney is quietly making excellent whisky and winning huge awards. Isn’t it time you raise your sails and explore some new territory?

Disclosure: Old Pulteney provided me with a complimentary tour and tasting. All thoughts and opinions expressed here, as always, are my own.

I was told by an Old Salt Scot that seawater is used in the distillation of Old Pourtney. Didn’t read anything about it in your report. Said OSS remarked each pull was like a breath of fresh salt air….

I can almost promise you (almost only because I don’t work at Old Pulteney) they do *not* use any seawater in the process. You can’t make whisky with saltwater. The water used in the production of Old Pulteney whisky comes from Loch Hempriggs. Many of their whiskies have a maritime element in the nosing and tasting, however, and that could be because the warehouse are subject to winds off the North Sea. Such an influence, however, is debatable within the industry.

What do you mean they ferment dry?

Fermenting dry means they allow the wort to ferment until there is no sugar left in it (i.e., the specific gravity is 1.000 or less). If you drank the resultant beer it would be ‘dry’ like a dry wine or cider. Fermenting dry reaps all the potential alcohol in the wort, which is good for distillation.

Hi Keith,

Love your descriptions. I’ll be looking for the 12 year old and 21 year old. Those two sound interesting and different! We are adding to our collection, and your posts have been extremely helpful in sorting out possible future buys.

Thanks again!

Glad to hear my posts are helping you expand!

What is meant by a “two-finger Old Pulteney”. My Danish friend mentions this in an email and as a Scot I don’t want to show my ignorance. Please please enlighten me. Thanks